by George Kesarios

Seeking Alpha

August 31, 2012

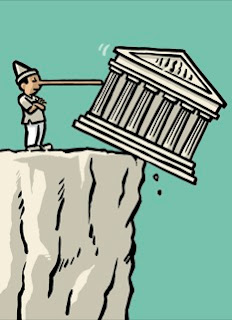

The recent Grexit rhetoric is not restricted to German officials, but to all European politicians across the board. My guess is that a lot of it has to do more with internal consumption politics in many European countries than with reality.

To try to make you understand why a Grexit is next to impossible, let's think about what will happen if Greece is actually kicked out of the European Monetary Union (EMU).

Aside from the legal issues, if Greece is indeed kicked out of the euro, that means that the deposits in euros which Greek citizens have in Greek banks will have no value. Actually, they will have some value, but not the current value of the euro.

This also means that if another country were to be kicked out of the euro, then the deposits of that country's citizens will also be worth something other than the euro's current value. In both cases, the value of the deposits will be worth a whole lot less.

As you understand, if Greece were to indeed be kicked out of the EMU, then that would set a precedent and that would mean that other countries, under certain circumstances, would also be able to be expelled. So if Greece gets kicked out, my hunch is that we would see a bank run of historic proportions all across Europe.

Which means that the euro would collapse, because depositors and investors would be running scared, speculating who will be next, probably buying dollars in the short term. In any case, I foresee a massive exodus from the euro across the board, including investors and depositors in Germany.

More

Friday, August 31, 2012

How to Prevent Euro Zone Contagion

by Kristina Peterson

Wall Street Journal

August 31, 2012

European Central Bank President Mario Draghi canceled his plans this week to attend the Kansas City Federal Reserve’s economic symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyo. But central bankers and academics gathering are discussing the crisis he faces.

Preventing the financial turmoil in one country from spreading to others — a process called contagion — requires different measures in the euro zone than in other regions, finds Kristin Forbes, an economics professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology‘s Sloan School of Management, in a paper to be presented at the conference on Friday.

Because the 17 countries in the euro zone share a currency and a central bank, they can’t individually adjust to shocks outside their borders through currency devaluation or monetary policy. That makes it more important for euro-zone countries to maintain flexible economies that can adjust quickly, she writes. That also may provide a little more justification for taking policy actions to help stop a chain of bad events that could unleash widespread damage, she writes. European leaders have been arguing for many years over what to do to stop the spread of rising government bond yields, capital flight, bank losses and other financial problems through the region.

More

Read the Paper

Wall Street Journal

August 31, 2012

European Central Bank President Mario Draghi canceled his plans this week to attend the Kansas City Federal Reserve’s economic symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyo. But central bankers and academics gathering are discussing the crisis he faces.

Preventing the financial turmoil in one country from spreading to others — a process called contagion — requires different measures in the euro zone than in other regions, finds Kristin Forbes, an economics professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology‘s Sloan School of Management, in a paper to be presented at the conference on Friday.

Because the 17 countries in the euro zone share a currency and a central bank, they can’t individually adjust to shocks outside their borders through currency devaluation or monetary policy. That makes it more important for euro-zone countries to maintain flexible economies that can adjust quickly, she writes. That also may provide a little more justification for taking policy actions to help stop a chain of bad events that could unleash widespread damage, she writes. European leaders have been arguing for many years over what to do to stop the spread of rising government bond yields, capital flight, bank losses and other financial problems through the region.

More

Read the Paper

For Greece a tear

Economist

August 31, 2012

The political mayhem which overtook Greece in the 1960s was avoidable and, in some ways, unexpected. Although the embers of a bitter left-right civil war were still smouldering, Hellenes began that decade in an upbeat mood. There seemed a decent chance that democracy would put down stronger roots in the land of its birth as prosperity grew.

Instead, one disaster followed another. The country’s future was furiously contested not only by scheming politicians but by other groups: street demonstrators, a politicised monarchy, the American embassy and foreign spooks. All this is subject to careful, intelligent analysis in a new biography of Andreas Papandreou by Stan Draenos, an American-based Greek historian and political scientist.

Using archives and interviews Mr Draenos studies every twist in the early political career of the man who later stormed to power as Greece’s first socialist leader in 1981. The book traces Papandreou's return to Greece in 1959 as an American-trained academic, his metamorphosis into a political firebrand, his imprisonment in 1967, followed a few months later by his expulsion from Greece and exile in Sweden. (The family's Swedish experience helped to mould Andreas’s son, George Papandreou, into a moderate social-democratic leader whose government fell victim to the euro crisis last year.)

More

August 31, 2012

The political mayhem which overtook Greece in the 1960s was avoidable and, in some ways, unexpected. Although the embers of a bitter left-right civil war were still smouldering, Hellenes began that decade in an upbeat mood. There seemed a decent chance that democracy would put down stronger roots in the land of its birth as prosperity grew.

Instead, one disaster followed another. The country’s future was furiously contested not only by scheming politicians but by other groups: street demonstrators, a politicised monarchy, the American embassy and foreign spooks. All this is subject to careful, intelligent analysis in a new biography of Andreas Papandreou by Stan Draenos, an American-based Greek historian and political scientist.

Using archives and interviews Mr Draenos studies every twist in the early political career of the man who later stormed to power as Greece’s first socialist leader in 1981. The book traces Papandreou's return to Greece in 1959 as an American-trained academic, his metamorphosis into a political firebrand, his imprisonment in 1967, followed a few months later by his expulsion from Greece and exile in Sweden. (The family's Swedish experience helped to mould Andreas’s son, George Papandreou, into a moderate social-democratic leader whose government fell victim to the euro crisis last year.)

More

Federalism or Bust for Europe?

by Jean Pisani-Ferry

Project Syndicate

August 31, 2012

August was quieter than feared on the European bond markets. So, while resting on Europe’s beaches and mountains, policymakers could take a step back from the sound and fury of the last few months and think about the future. Is the eurozone sleepwalking into becoming a United States of Europe? Is it exploring uncharted territory? Or are its constituent nation-states drifting apart?

To answer these questions, the best starting point is the US. The model of a federal union that emerged from its history consists of a single currency managed by a federal agency; closely integrated markets for products, labor, and capital; a federal budget that partly, but automatically, offsets economic disturbances affecting individual states; a federal government that assumes responsibility for tackling other major risks, not least those emanating from the banking sector; and states that provide regional public goods but play virtually no role in macroeconomic stabilization.

This model served as a template for the European Union’s architects, notably for the creation of a unified market and a common currency. But, in several respects, Europe has diverged significantly from the American model.

More

Project Syndicate

August 31, 2012

August was quieter than feared on the European bond markets. So, while resting on Europe’s beaches and mountains, policymakers could take a step back from the sound and fury of the last few months and think about the future. Is the eurozone sleepwalking into becoming a United States of Europe? Is it exploring uncharted territory? Or are its constituent nation-states drifting apart?

To answer these questions, the best starting point is the US. The model of a federal union that emerged from its history consists of a single currency managed by a federal agency; closely integrated markets for products, labor, and capital; a federal budget that partly, but automatically, offsets economic disturbances affecting individual states; a federal government that assumes responsibility for tackling other major risks, not least those emanating from the banking sector; and states that provide regional public goods but play virtually no role in macroeconomic stabilization.

This model served as a template for the European Union’s architects, notably for the creation of a unified market and a common currency. But, in several respects, Europe has diverged significantly from the American model.

More

Τράπεζες και τραπεζίτες

του Τάσου Τέλλογλου

Protagon.gr

31 Αυγούστου 2012

Ο κ. Παναγιώτης Λαφαζάνης μίλησε στην αρμόδια επιτροπή της Βουλής για «ληστεία του ελληνικού λαού» σε όφελος των τραπεζιτών όταν ο υπουργός Οικονομικών κ. Γιάννης Στουρνάρας μίλησε για τους όρους της ανακεφαλαιοποίησης των τραπεζών. Η ρητορική είναι δωρεάν βεβαίως διότι ο κ Λαφαζάνης δεν μπορεί να αγνοεί ότι οι ελληνικές τράπεζες εχουν πάρει 150 δισεκατομμύρια από την ΕΚΤ και ότι χάρη σε αυτά παραμένουν σε λειτουργία -διαφορετικά θα είχαν κλείσει, οι θέσεις εργασίας και οι καταθέσεις θα είχαν εξαφανισθεί. Δεν είναι ίσως σωστό να λέγεται δημόσια αλλά σήμερα το δημόσιο δεν είναι σε θέση χωρίς την Ευρώπη να υλοποιήσει την εγγύηση των καταθέσεων για την οποία εχει δεσμευθεί.

Και για αυτό δεν ευθύνονται κυρίως οι Τράπεζες αλλά το κράτος και οι ψηφοφόροι των κομμάτων που – πολλοί ασφαλώς από αντικειμενική αδυναμία - δεν είναι συνεπείς προς τις υποχρεώσεις τους, δεν πληρώνουν δηλαδή. Από την επόμενη πολυπόθητη δόση, 25 (από τα 31 δισεκατομμύρια) θα δοθούν για την ανακεφαλαιοποίηση των τραπεζών. Η αρχική επιδιωξη ορισμένων διοικήσεων ιδιωτικών τραπεζών να γίνει η ανακεφαλαιοποίηση με τους όρους τους δεν «περασε» χάρη στην παρεμβαση της ΤτΕ και του κ Στουρνάρα.

Περισσότερα

Protagon.gr

31 Αυγούστου 2012

Ο κ. Παναγιώτης Λαφαζάνης μίλησε στην αρμόδια επιτροπή της Βουλής για «ληστεία του ελληνικού λαού» σε όφελος των τραπεζιτών όταν ο υπουργός Οικονομικών κ. Γιάννης Στουρνάρας μίλησε για τους όρους της ανακεφαλαιοποίησης των τραπεζών. Η ρητορική είναι δωρεάν βεβαίως διότι ο κ Λαφαζάνης δεν μπορεί να αγνοεί ότι οι ελληνικές τράπεζες εχουν πάρει 150 δισεκατομμύρια από την ΕΚΤ και ότι χάρη σε αυτά παραμένουν σε λειτουργία -διαφορετικά θα είχαν κλείσει, οι θέσεις εργασίας και οι καταθέσεις θα είχαν εξαφανισθεί. Δεν είναι ίσως σωστό να λέγεται δημόσια αλλά σήμερα το δημόσιο δεν είναι σε θέση χωρίς την Ευρώπη να υλοποιήσει την εγγύηση των καταθέσεων για την οποία εχει δεσμευθεί.

Και για αυτό δεν ευθύνονται κυρίως οι Τράπεζες αλλά το κράτος και οι ψηφοφόροι των κομμάτων που – πολλοί ασφαλώς από αντικειμενική αδυναμία - δεν είναι συνεπείς προς τις υποχρεώσεις τους, δεν πληρώνουν δηλαδή. Από την επόμενη πολυπόθητη δόση, 25 (από τα 31 δισεκατομμύρια) θα δοθούν για την ανακεφαλαιοποίηση των τραπεζών. Η αρχική επιδιωξη ορισμένων διοικήσεων ιδιωτικών τραπεζών να γίνει η ανακεφαλαιοποίηση με τους όρους τους δεν «περασε» χάρη στην παρεμβαση της ΤτΕ και του κ Στουρνάρα.

Περισσότερα

Thursday, August 30, 2012

The Roadmap to Banking Union: A Call for Consistency

by Karel Lannoo

Centre for European Policy Studies

August 30, 2012

The proposal to move to a full banking union in the eurozone means a radical regime shift for the EU, since the European Central Bank will supervise the eurozone banks and effectively end ‘home country rule’. But how this is implemented raises a number of questions and needs close monitoring, explains CEPS CEO Karel Lannoo in this new Commentary.

Read the Paper

Centre for European Policy Studies

August 30, 2012

The proposal to move to a full banking union in the eurozone means a radical regime shift for the EU, since the European Central Bank will supervise the eurozone banks and effectively end ‘home country rule’. But how this is implemented raises a number of questions and needs close monitoring, explains CEPS CEO Karel Lannoo in this new Commentary.

Read the Paper

Οι έξυπνοι με τις εύκολες λύσεις

του Στέφανου Κασιμάτη

Καθημερινή

30 Αυγούστου 2012

«Εσείς τι θα κάνατε για να πετύχετε τους στόχους στους οποίους λέτε ότι αποτυγχάνει η κυβέρνηση;» Είναι η ερώτηση που ευλόγως ακολουθεί το στερεότυπο, μακρόσυρτο κήρυγμα κατά της πολιτικής του Μνημονίου από τον μονίμως περιοδεύοντα στα ραδιοφωνικά μικρόφωνα βουλευτή του ΣΥΡΙΖΑ, του οποίου το όνομα δεν έχει σημασία. Εκείνος τότε παίρνει το σύνηθες, γλοιώδες, δασκαλίστικο ύφος του -αυτό που υποτίθεται ότι ταιριάζει με την ηθική και πνευματική ανωτερότητα της Αριστεράς- και, χαμηλώνοντας λίγο την ένταση της φωνής, σαν να πρόκειται να μας αποκαλύψει το μεγάλο μυστικό, αρχίζει να εξηγεί στα «παιδάκια» του ραδιοφωνικού ακροατηρίου ότι θα πατάξουν τη φοροδιαφυγή με ένα δίκαιο φορολογικό σύστημα, θα κόψουν στο Δημόσιο τις «περιττές σπατάλες» (λες και υπάρχουν... αναγκαίες σπατάλες) και άλλα ηχηρά παρόμοια.

Είναι τα συνήθη φούμαρα αυτά· τα ακούμε χρόνια τώρα από κυβερνήσεις είτε της Κεντροαριστεράς είτε της Κεντροδεξιάς. Είτε με τη μορφή του «άλλου δρόμου» (τρίτου, τέταρτου, πέμπτου; - έχω χάσει πια το μέτρημα...) είτε στην εκδοχή της ηθικής προσταγής για «σεμνότητα και ταπεινότητα», η ουσία τους συμπυκνώνεται πάντα στον βλακώδη ισχυρισμό ότι υπάρχει κάποιος δήθεν μαγικός τρόπος -ο οποίος, παρεμπιπτόντως, ποτέ δεν εξηγείται σαφώς και πουθενά αλλού δεν έχει εφαρμοσθεί- να φτιάξουμε καλύτερους ανθρώπους. Αυτό ήταν πάντοτε η απάντηση των κυβερνήσεων της πασοκαρίας, πράσινης και γαλάζιας, μπροστά στα προβλήματα. Ως στάση είχε την εξήγησή της: ούτε οι μεν ούτε οι δε ήθελαν να αλλάξει τίποτε, διότι πολύ απλά δεν ήθελαν να πάψουν να νέμονται τα οφέλη από τη σχέση κράτους, κόμματος και οικονομίας, που με τα χρόνια είχε εξελιχθεί σε ένα σύμπλεγμα σχεδόν αξιεδάλυτο. Σχεδόν, όπως είπα - διότι έπειτα ήλθε η κρίση και ο μύθος που ζούσαμε στην Ελλάδα τελείωσε.

Οχι όμως και για την Αριστερά του Τσίπρα: γι’ αυτούς ο μύθος δεν έχει τελειώσει. Διότι, καθώς οι άλλοι ψελλίζουν ως επί το πλείστον ακαταλαβίστικες ασυναρτησίες, για να κρυφτούν από την αλήθεια που τους εκθέτει, η Αριστερά του Τσίπρα το μόνο που έχει να εισφέρει στη συζήτηση για το τι κάνουμε τώρα είναι τη δική της εκδοχή της φουμαρολογίας του παρελθόντος. Ποια ανώδυνη εξοικονόμηση πόρων, δηλαδή, μπορούν να κάνουν οι φωστήρες του ΣΥΡΙΖΑ και γιατί δεν μπόρεσαν να την κάνουν οι κυβερνήσεις των δύο τελευταίων χρόνων; Μήπως επειδή τους αρέσει και το μαστίγιο της τρόικας να νιώθουν και τις κατώτερες συντάξεις να κόβουν και τις υποχρεώσεις του Δημοσίου προς τους ιδιώτες να αφήνουν απλήρωτες; Εχουν την απαίτηση, με άλλα λόγια, να πιστέψουμε ότι τα τρία κόμματα που συγκυβερνούν σήμερα είναι οι μαζοχιστές της αυτοκαταστροφής, ενώ ο ΣΥΡΙΖΑ είναι οι έξυπνοι με τις εύκολες λύσεις; Μόνον οι ανόητοι θα το πίστευαν...

Περισσότερα

Καθημερινή

30 Αυγούστου 2012

«Εσείς τι θα κάνατε για να πετύχετε τους στόχους στους οποίους λέτε ότι αποτυγχάνει η κυβέρνηση;» Είναι η ερώτηση που ευλόγως ακολουθεί το στερεότυπο, μακρόσυρτο κήρυγμα κατά της πολιτικής του Μνημονίου από τον μονίμως περιοδεύοντα στα ραδιοφωνικά μικρόφωνα βουλευτή του ΣΥΡΙΖΑ, του οποίου το όνομα δεν έχει σημασία. Εκείνος τότε παίρνει το σύνηθες, γλοιώδες, δασκαλίστικο ύφος του -αυτό που υποτίθεται ότι ταιριάζει με την ηθική και πνευματική ανωτερότητα της Αριστεράς- και, χαμηλώνοντας λίγο την ένταση της φωνής, σαν να πρόκειται να μας αποκαλύψει το μεγάλο μυστικό, αρχίζει να εξηγεί στα «παιδάκια» του ραδιοφωνικού ακροατηρίου ότι θα πατάξουν τη φοροδιαφυγή με ένα δίκαιο φορολογικό σύστημα, θα κόψουν στο Δημόσιο τις «περιττές σπατάλες» (λες και υπάρχουν... αναγκαίες σπατάλες) και άλλα ηχηρά παρόμοια.

Είναι τα συνήθη φούμαρα αυτά· τα ακούμε χρόνια τώρα από κυβερνήσεις είτε της Κεντροαριστεράς είτε της Κεντροδεξιάς. Είτε με τη μορφή του «άλλου δρόμου» (τρίτου, τέταρτου, πέμπτου; - έχω χάσει πια το μέτρημα...) είτε στην εκδοχή της ηθικής προσταγής για «σεμνότητα και ταπεινότητα», η ουσία τους συμπυκνώνεται πάντα στον βλακώδη ισχυρισμό ότι υπάρχει κάποιος δήθεν μαγικός τρόπος -ο οποίος, παρεμπιπτόντως, ποτέ δεν εξηγείται σαφώς και πουθενά αλλού δεν έχει εφαρμοσθεί- να φτιάξουμε καλύτερους ανθρώπους. Αυτό ήταν πάντοτε η απάντηση των κυβερνήσεων της πασοκαρίας, πράσινης και γαλάζιας, μπροστά στα προβλήματα. Ως στάση είχε την εξήγησή της: ούτε οι μεν ούτε οι δε ήθελαν να αλλάξει τίποτε, διότι πολύ απλά δεν ήθελαν να πάψουν να νέμονται τα οφέλη από τη σχέση κράτους, κόμματος και οικονομίας, που με τα χρόνια είχε εξελιχθεί σε ένα σύμπλεγμα σχεδόν αξιεδάλυτο. Σχεδόν, όπως είπα - διότι έπειτα ήλθε η κρίση και ο μύθος που ζούσαμε στην Ελλάδα τελείωσε.

Οχι όμως και για την Αριστερά του Τσίπρα: γι’ αυτούς ο μύθος δεν έχει τελειώσει. Διότι, καθώς οι άλλοι ψελλίζουν ως επί το πλείστον ακαταλαβίστικες ασυναρτησίες, για να κρυφτούν από την αλήθεια που τους εκθέτει, η Αριστερά του Τσίπρα το μόνο που έχει να εισφέρει στη συζήτηση για το τι κάνουμε τώρα είναι τη δική της εκδοχή της φουμαρολογίας του παρελθόντος. Ποια ανώδυνη εξοικονόμηση πόρων, δηλαδή, μπορούν να κάνουν οι φωστήρες του ΣΥΡΙΖΑ και γιατί δεν μπόρεσαν να την κάνουν οι κυβερνήσεις των δύο τελευταίων χρόνων; Μήπως επειδή τους αρέσει και το μαστίγιο της τρόικας να νιώθουν και τις κατώτερες συντάξεις να κόβουν και τις υποχρεώσεις του Δημοσίου προς τους ιδιώτες να αφήνουν απλήρωτες; Εχουν την απαίτηση, με άλλα λόγια, να πιστέψουμε ότι τα τρία κόμματα που συγκυβερνούν σήμερα είναι οι μαζοχιστές της αυτοκαταστροφής, ενώ ο ΣΥΡΙΖΑ είναι οι έξυπνοι με τις εύκολες λύσεις; Μόνον οι ανόητοι θα το πίστευαν...

Περισσότερα

Democracies and debt: Voters are now facing a harsh truth

Economist

September 1, 2012

Almost half the world’s population now lives in a democracy, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit, a sister organisation of this newspaper. And the number of democracies has increased pretty steadily since the second world war. But it is easy to forget that most nations have not been democratic for much of their history and that, for a long time, democracy was a dirty word among political philosophers.

One reason was the fear that democratic rule would lead to ruin. Plato warned that democratic leaders would “rob the rich, keep as much of the proceeds as they can for themselves and distribute the rest to the people”. James Madison, one of America’s founding fathers, feared that democracy would lead to “a rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property and for any other improper or wicked projects”. Similarly John Adams, the country’s second president, worried that rule by the masses would lead to heavy taxes on the rich in the name of equality. As a consequence, “the idle, the vicious, the intemperate would rush into the utmost extravagance of debauchery, sell and spend all their share, and then demand a new division of those who purchased from them.”

Democracy may have its faults but alternative systems have proved no more fiscally prudent. Dictatorships may still feel the need to bribe their citizens (eg, via subsidised fuel prices) to ensure their acquiescence while simultaneously spending large amounts on the police and the military to shore up their power. The absolute monarchies of Spain and France suffered fiscal crises in the 17th and 18th centuries, and were challenged by Britain and the Netherlands which, though not yet democracies, had dispersed power more widely. Financial problems contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

More

September 1, 2012

Almost half the world’s population now lives in a democracy, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit, a sister organisation of this newspaper. And the number of democracies has increased pretty steadily since the second world war. But it is easy to forget that most nations have not been democratic for much of their history and that, for a long time, democracy was a dirty word among political philosophers.

One reason was the fear that democratic rule would lead to ruin. Plato warned that democratic leaders would “rob the rich, keep as much of the proceeds as they can for themselves and distribute the rest to the people”. James Madison, one of America’s founding fathers, feared that democracy would lead to “a rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property and for any other improper or wicked projects”. Similarly John Adams, the country’s second president, worried that rule by the masses would lead to heavy taxes on the rich in the name of equality. As a consequence, “the idle, the vicious, the intemperate would rush into the utmost extravagance of debauchery, sell and spend all their share, and then demand a new division of those who purchased from them.”

Democracy may have its faults but alternative systems have proved no more fiscally prudent. Dictatorships may still feel the need to bribe their citizens (eg, via subsidised fuel prices) to ensure their acquiescence while simultaneously spending large amounts on the police and the military to shore up their power. The absolute monarchies of Spain and France suffered fiscal crises in the 17th and 18th centuries, and were challenged by Britain and the Netherlands which, though not yet democracies, had dispersed power more widely. Financial problems contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

More

Ξαφνικός έρωτας για την Ελλάδα;

του Σήφη Πολυμίλη

Το Βήμα

30 Αυγούστου 2012

Λέτε να μας αγάπησαν ξαφνικά οι ευρωπαίοι και οι δηλώσεις υπεράσπισης ακολουθούν η μια μετά την άλλη;Πως γίνεται εκεί που μέχρι πριν λίγες εβδομάδες βρισκόμαστε μονίμως στο στόχαστρο κάθε λογής πολιτικολογούντων και δημοσιολογούντων,να έχει αντιστραφεί το κλίμα και σχεδόν οι πάντες να αναγνωρίζουν και να επενδύουν στην παραμονή της Ελλάδας στην ευρωζώνη;

Μόνο χθες είχαμε το γάλλο πρωθυπουργό να δηλώνει ότι οι ευρωπαίοι είναι «αποφασισμένοι να κάνουν τα πάντα για να βεβαιωθούν ότι η Ελλάδα θα παραμείνει στο ευρώ",τον ηγέτη των γερμανών σοσιαλδημοκρατών να προειδοποιεί ότι " πλανάται όποιος νομίζει ότι η έξοδος της Ελλάδας από το ευρώ θα διευκολύνει την κατάσταση» και βέβαια να μην ξεχάσουμε τη θλίψη της κυρίας Μέρκελ για τον πόνο που υφίστανται οι έλληνες πολίτες...

Προφανώς ούτε μας αγάπησαν, ούτε μας λυπήθηκαν περισσότερο ξαφνικά.Φαίνεται όμως ότι επιτέλους κάτι αρχίζει να κινείται στην Ευρώπη ,ότι μια πιο παρεμβατική πολιτική βρίσκεται στα σκαριά, που μπορεί να δώσει και σε μας την ευκαιρία που αναζητούμε ,για να πάρουμε μια ανάσα.

Περισσότερα

Το Βήμα

30 Αυγούστου 2012

Λέτε να μας αγάπησαν ξαφνικά οι ευρωπαίοι και οι δηλώσεις υπεράσπισης ακολουθούν η μια μετά την άλλη;Πως γίνεται εκεί που μέχρι πριν λίγες εβδομάδες βρισκόμαστε μονίμως στο στόχαστρο κάθε λογής πολιτικολογούντων και δημοσιολογούντων,να έχει αντιστραφεί το κλίμα και σχεδόν οι πάντες να αναγνωρίζουν και να επενδύουν στην παραμονή της Ελλάδας στην ευρωζώνη;

Μόνο χθες είχαμε το γάλλο πρωθυπουργό να δηλώνει ότι οι ευρωπαίοι είναι «αποφασισμένοι να κάνουν τα πάντα για να βεβαιωθούν ότι η Ελλάδα θα παραμείνει στο ευρώ",τον ηγέτη των γερμανών σοσιαλδημοκρατών να προειδοποιεί ότι " πλανάται όποιος νομίζει ότι η έξοδος της Ελλάδας από το ευρώ θα διευκολύνει την κατάσταση» και βέβαια να μην ξεχάσουμε τη θλίψη της κυρίας Μέρκελ για τον πόνο που υφίστανται οι έλληνες πολίτες...

Προφανώς ούτε μας αγάπησαν, ούτε μας λυπήθηκαν περισσότερο ξαφνικά.Φαίνεται όμως ότι επιτέλους κάτι αρχίζει να κινείται στην Ευρώπη ,ότι μια πιο παρεμβατική πολιτική βρίσκεται στα σκαριά, που μπορεί να δώσει και σε μας την ευκαιρία που αναζητούμε ,για να πάρουμε μια ανάσα.

Περισσότερα

Europe's Love-Hate Relationship With Financial Markets

by Richard Barley

Wall Street Journal

August 29, 2012

Why does Europe persist in biting the hand that funds it?

European Council President Herman Van Rompuy this week warned of "defiance" by financial markets as countries undertake much-needed policy adjustments. The idea that markets are somehow attacking the euro zone has been understandably popular among politicians seeking to apportion blame. But it is one that should have been discarded by now.

Mr. van Rompuy didn't explain exactly what this "defiance" consisted of. But he said Europe was ready to help Spain further if it persists, in other words, if investors continue to shy away from buying Spanish bonds. Mr. van Rompuy argues that the measures being undertaken by Europe and Spain will clarify the situation of Spain's banking system, restore confidence and stimulate the Spanish economy.

The trouble is institutional investors have reason to be skeptical. It is hardly "defiance" to decline to put other people's cash at risk in Spanish government bonds, given the euro zone's history of grand solutions to the debt crisis that have failed. In fact, given the high level of yields, it is painful for investors not to hold Spanish bonds if they are benchmarked against indexes that include Spain.

More

Wall Street Journal

August 29, 2012

Why does Europe persist in biting the hand that funds it?

European Council President Herman Van Rompuy this week warned of "defiance" by financial markets as countries undertake much-needed policy adjustments. The idea that markets are somehow attacking the euro zone has been understandably popular among politicians seeking to apportion blame. But it is one that should have been discarded by now.

Mr. van Rompuy didn't explain exactly what this "defiance" consisted of. But he said Europe was ready to help Spain further if it persists, in other words, if investors continue to shy away from buying Spanish bonds. Mr. van Rompuy argues that the measures being undertaken by Europe and Spain will clarify the situation of Spain's banking system, restore confidence and stimulate the Spanish economy.

The trouble is institutional investors have reason to be skeptical. It is hardly "defiance" to decline to put other people's cash at risk in Spanish government bonds, given the euro zone's history of grand solutions to the debt crisis that have failed. In fact, given the high level of yields, it is painful for investors not to hold Spanish bonds if they are benchmarked against indexes that include Spain.

More

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

Greece grinds on

Financial Times

Editorial

August 29, 2012

The late-summer diplomacy over Greece is so far having less impact on the country’s future in the eurozone than its economic situation, which continues to change – mostly for the worse, but also in ways that may defy the sceptics.

Antonis Samaras, the Greek prime minister, last week met with German chancellor Angela Merkel and French president François Hollande. They reiterated their broad support for Greece’s place within the single currency, but offered no help beyond the current rescue programme. In particular, they declined – for now – to grant Mr Samaras’s request to stretch out remaining austerity measures over four years instead of two.

This was predictable. Berlin (if not the Bundesbank) and Paris have aligned themselves with the European Central Bank’s preparations to intervene in government bond markets and are well advised to see how that plays out before their next move. Offering Athens anything before the creditor troika finishes its assessment this autumn is politically impossible at home and tactically unwise vis a vis Mr Samaras’s government. If Athens shows it means business, however, the extension should be granted but with no extra funding.

As the wheels of diplomacy whir on, the cogs of the Greek economy are grinding out a new reality. Austerity and a European slowdown have depressed the economy and kept pushing headline deficit goals out of reach. But Athens has done more than many think. Unit labour costs are falling and the primary deficit – before debt service costs – is almost gone.

More

Editorial

August 29, 2012

The late-summer diplomacy over Greece is so far having less impact on the country’s future in the eurozone than its economic situation, which continues to change – mostly for the worse, but also in ways that may defy the sceptics.

Antonis Samaras, the Greek prime minister, last week met with German chancellor Angela Merkel and French president François Hollande. They reiterated their broad support for Greece’s place within the single currency, but offered no help beyond the current rescue programme. In particular, they declined – for now – to grant Mr Samaras’s request to stretch out remaining austerity measures over four years instead of two.

This was predictable. Berlin (if not the Bundesbank) and Paris have aligned themselves with the European Central Bank’s preparations to intervene in government bond markets and are well advised to see how that plays out before their next move. Offering Athens anything before the creditor troika finishes its assessment this autumn is politically impossible at home and tactically unwise vis a vis Mr Samaras’s government. If Athens shows it means business, however, the extension should be granted but with no extra funding.

As the wheels of diplomacy whir on, the cogs of the Greek economy are grinding out a new reality. Austerity and a European slowdown have depressed the economy and kept pushing headline deficit goals out of reach. But Athens has done more than many think. Unit labour costs are falling and the primary deficit – before debt service costs – is almost gone.

More

The European Tragedy

by Stephen Davies

Freeman

September 2012

People are closely watching the slow-motion train wreck that is the crisis of the eurozone—that is, the economic travails of Greece, Spain, Ireland, Portugal, and Italy (known collectively as the PIIGS). The problem with much of the discussion in the United States is that both of the main camps are right about some things but wrong about others because neither fully grasps the real nature and cause of the crisis in Europe.

One view holds up the Europeans as a warning to the United States of the consequences of government profligacy. The problem, so the argument goes, is crushing sovereign debt brought about by excessive government spending over many years funded by borrowing rather than taxation. The rising yields on sovereign debt reflect that investors now realize the European governments are bankrupt and cannot be relied on to service their accumulated debt, much less repay it. As yields rise the burden of debt becomes greater until the only ways out are either default or fiscal stringency with a combination of tax increases and cuts in government spending to bring stability. This is also the view, it would appear, of the German finance ministry and much of the German public.

The contrary view is that the European crisis is indeed a warning to the United States—of the dreadful consequences of austerity. For this camp the experience shows the folly of responding to the financial crisis of 2007–08 with cuts in government spending and efforts at balancing the books. These efforts are self-defeating because they will aggravate the economic contraction and reduce government revenues while increasing spending (because of “automatic stabilizers” such as unemployment benefits), worsening the government’s finances. The correct response to the economic slowdown in Europe, therefore, is a Keynesian one of increasing government spending and widening deficits, at least in the short term, until the economy recovers.

More

Freeman

September 2012

People are closely watching the slow-motion train wreck that is the crisis of the eurozone—that is, the economic travails of Greece, Spain, Ireland, Portugal, and Italy (known collectively as the PIIGS). The problem with much of the discussion in the United States is that both of the main camps are right about some things but wrong about others because neither fully grasps the real nature and cause of the crisis in Europe.

One view holds up the Europeans as a warning to the United States of the consequences of government profligacy. The problem, so the argument goes, is crushing sovereign debt brought about by excessive government spending over many years funded by borrowing rather than taxation. The rising yields on sovereign debt reflect that investors now realize the European governments are bankrupt and cannot be relied on to service their accumulated debt, much less repay it. As yields rise the burden of debt becomes greater until the only ways out are either default or fiscal stringency with a combination of tax increases and cuts in government spending to bring stability. This is also the view, it would appear, of the German finance ministry and much of the German public.

The contrary view is that the European crisis is indeed a warning to the United States—of the dreadful consequences of austerity. For this camp the experience shows the folly of responding to the financial crisis of 2007–08 with cuts in government spending and efforts at balancing the books. These efforts are self-defeating because they will aggravate the economic contraction and reduce government revenues while increasing spending (because of “automatic stabilizers” such as unemployment benefits), worsening the government’s finances. The correct response to the economic slowdown in Europe, therefore, is a Keynesian one of increasing government spending and widening deficits, at least in the short term, until the economy recovers.

More

The Euro Crisis Is Back From Vacation

by Adam Davidson

New York Times

August 28, 2012

In June, it seemed as if any day might bring about the collapse of the Greek economy and with it, the entire euro zone and its decade-old currency. Then in July and August, it seemed as if everyone was on vacation. Now they’re back — finance officials and political leaders have been flying all over Europe to meet with one another — and along with them the crisis that has been raging for the last two years. Here is a guide to the new season’s most intriguing (and terrifying) story lines.

1. What’s the first big matchup?

This month, Greece’s Parliament needs to approve an additional 11.5 billion euros in spending cuts for 2013-14. If it does, it will most likely prompt big protests in the streets. If it doesn’t, the so-called troika (the European Commission, the I.M.F. and the European Central Bank) won’t lend Greece the money to keep its economy afloat. If all sides get through September intact, they’ll still be at loggerheads during the next phase of budget negotiations.

More

New York Times

August 28, 2012

In June, it seemed as if any day might bring about the collapse of the Greek economy and with it, the entire euro zone and its decade-old currency. Then in July and August, it seemed as if everyone was on vacation. Now they’re back — finance officials and political leaders have been flying all over Europe to meet with one another — and along with them the crisis that has been raging for the last two years. Here is a guide to the new season’s most intriguing (and terrifying) story lines.

1. What’s the first big matchup?

This month, Greece’s Parliament needs to approve an additional 11.5 billion euros in spending cuts for 2013-14. If it does, it will most likely prompt big protests in the streets. If it doesn’t, the so-called troika (the European Commission, the I.M.F. and the European Central Bank) won’t lend Greece the money to keep its economy afloat. If all sides get through September intact, they’ll still be at loggerheads during the next phase of budget negotiations.

More

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Milton Friedman's prophetic article written 15 years ago: "The Euro: Monetary Unity To Political Disunity?"

by Milton Friedman

Project Syndicate

August 28, 1997

A common currency is an excellent monetary arrangement under some circumstances, a poor monetary arrangement under others. Whether it is good or bad depends primarily on the adjustment mechanisms that are available to absorb the economic shocks and dislocations that impinge on the various entities that are considering a common currency. Flexible exchange rates are a powerful adjustment mechanism for shocks that affect the entities differently. It is worth dispensing with this mechanism to gain the advantage of lower transaction costs and external discipline only if there are adequate alternative adjustment mechanisms.

The United States is an example of a situation that is favorable to a common currency. Though composed of fifty states, its residents overwhelmingly speak the same language, listen to the same television programs, see the same movies, can and do move freely from one part of the country to another; goods and capital move freely from state to state; wages and prices are moderately flexible; and the national government raises in taxes and spends roughly twice as much as state and local governments. Fiscal policies differ from state to state, but the differences are minor compared to the common national policy.

Unexpected shocks may well affect one part of the United States more than others -- as, for example, the Middle East embargo on oil did in the 1970s, creating an increased demand for labor and boom conditions in some states, such as Texas, and unemployment and depressed conditions in others, such as the oil-importing states of the industrial Midwest. The different short-run effects were soon mediated by movements of people and goods, by offsetting financial flows from the national to the state and local governments, and by adjustments in prices and wages.

By contrast, Europe’s common market exemplifies a situation that is unfavorable to a common currency. It is composed of separate nations, whose residents speak different languages, have different customs, and have far greater loyalty and attachment to their own country than to the common market or to the idea of "Europe." Despite being a free trade area, goods move less freely than in the United States, and so does capital.

More

Project Syndicate

August 28, 1997

A common currency is an excellent monetary arrangement under some circumstances, a poor monetary arrangement under others. Whether it is good or bad depends primarily on the adjustment mechanisms that are available to absorb the economic shocks and dislocations that impinge on the various entities that are considering a common currency. Flexible exchange rates are a powerful adjustment mechanism for shocks that affect the entities differently. It is worth dispensing with this mechanism to gain the advantage of lower transaction costs and external discipline only if there are adequate alternative adjustment mechanisms.

The United States is an example of a situation that is favorable to a common currency. Though composed of fifty states, its residents overwhelmingly speak the same language, listen to the same television programs, see the same movies, can and do move freely from one part of the country to another; goods and capital move freely from state to state; wages and prices are moderately flexible; and the national government raises in taxes and spends roughly twice as much as state and local governments. Fiscal policies differ from state to state, but the differences are minor compared to the common national policy.

Unexpected shocks may well affect one part of the United States more than others -- as, for example, the Middle East embargo on oil did in the 1970s, creating an increased demand for labor and boom conditions in some states, such as Texas, and unemployment and depressed conditions in others, such as the oil-importing states of the industrial Midwest. The different short-run effects were soon mediated by movements of people and goods, by offsetting financial flows from the national to the state and local governments, and by adjustments in prices and wages.

By contrast, Europe’s common market exemplifies a situation that is unfavorable to a common currency. It is composed of separate nations, whose residents speak different languages, have different customs, and have far greater loyalty and attachment to their own country than to the common market or to the idea of "Europe." Despite being a free trade area, goods move less freely than in the United States, and so does capital.

More

A German Sovereign Wealth Fund to save the euro

by Daniel Gros and Thomas Mayer

Vox

August 28, 2012

August 28, 2012

Large German trade surpluses are ingrained in the Eurozone’s structure, but private sector mechanisms for dealing with the corresponding capital account deficit are broken. The unavoidable result has been large official capital account deficits by Germany (the bailouts) and the Eurosystem (Target2 balances). This column proposes the creation of a Germany sovereign wealth fund that would restart the private recycling of Germany’s excess savings – eventually cleaning out the Target2 imbalances and depreciating the euro in the process.

Since the early 1950s, German savings have tended to exceed investment with the inevitable result that that Germans have, on net, been investing in foreign assets.

More

Vox

August 28, 2012

August 28, 2012Large German trade surpluses are ingrained in the Eurozone’s structure, but private sector mechanisms for dealing with the corresponding capital account deficit are broken. The unavoidable result has been large official capital account deficits by Germany (the bailouts) and the Eurosystem (Target2 balances). This column proposes the creation of a Germany sovereign wealth fund that would restart the private recycling of Germany’s excess savings – eventually cleaning out the Target2 imbalances and depreciating the euro in the process.

Since the early 1950s, German savings have tended to exceed investment with the inevitable result that that Germans have, on net, been investing in foreign assets.

- Most of these excess savings have been intermediated by the domestic banking system.

- With the advent of the euro, exchange rate risk within the Eurozone disappeared and German surpluses vis-à-vis EZ partner countries could and did become much larger.

- Large surpluses seem to have become structurally ingrained at a whopping 6% of GDP; that is more than a quarter of national savings.

More

Monday, August 27, 2012

Η έκθεση της τρόικας

του Τάκη Μίχα

Protagon.gr

27 Αυγούστου 2012

Δεν υπάρχει καμία αμφιβολία ότι η αναμενόμενη τον Σεπτέμβριο(;) έκθεση της τρόικα θα παίξει καθοριστικό ρόλο τόσο στην εξέλιξη της ιστορίας της Ελλάδας όσο και στην εξέλιξη της ευρωζώνης.

Οσον αφορά την Ελλάδα τα πορίσματα της έκθεσης δεν θα επηρεάσουν απλά το αν θα δοθεί στην Ελλάδα επιμήκυνση όσον αφορά την επίτευξη των στόχων στους οποίους έχει συμφωνήσει. Αυτό είναι ένα τελείως δευτερεύον θέμα. Τα πορίσματα της έκθεσης θα παίξουν καθοριστικό ρόλο για την παραμονή της Ελλάδας στην ευρωζώνη. Οχι επειδή μία τυχόν αρνητική έκθεση θα δώσει την ευκαιρία στους «εχθρούς» να μας «τιμωρήσουν», όπως διατείνεται η λαϊκή σοφία, αλλά επειδή απλούστατα μια τέτοια εξέλιξη θα πείσει τις χρηματαγορές ότι η έξοδος από το ευρώ είναι πλέον μη αντιστρέψιμη. Αυτό σημαίνει σε απλά ρωμέικα ότι κανένας δυνητικός επενδυτής, Ελληνας ή ξένος, δεν πρόκειται να επενδύσει στην Ελλάδα γνωρίζοντας ότι το κεφάλαιο του μπορεί να μειωθεί από την μία ημέρα στην άλλη κατά πιθανώς 50%. Και από την στιγμή που δεν θα υπάρχουν επενδύσεις όσα (καθυστερημένα) μέτρα και να λάβεις, όσες δηλώσεις συμπαράστασης και να γίνονται από τους ξένους ηγέτες, ανάκαμψη δεν πρόκειται να υπάρξει. Με αποτέλεσμα την νομοτελειακή εγκατάλειψη του ευρώ.

Όμως μία αρνητική για την Ελλάδα έκθεση της τρόικα θα έχει σημαντικές επιπτώσεις και στην ευρωζώνη. Στον βαθμό που θα ενισχύσει τις προσδοκίες των αγορών για έξοδο της Ελλάδας από το ευρώ, η συνεχιζόμενη παραμονή της θα δρά τελείως αποσταθεροποιητικά για την υπόλοιπη ευρωζώνη. Το θέμα δεν είναι ότι δεν θα γίνονται μόνο επενδύσεις στην Ελλάδα αλλά ούτε και στην υπόλοιπη ευρωζώνη καθώς όλοι θα περιμένουν να δούν τις επιπτώσεις που θα έχει η προεξοφλούμενη έξοδος της Ελλάδας. Απ' αυτή λοιπόν την σκοπιά η συνεχιζόμενη μετά από μία αρνητική έκθεση παραμονή της Ελλάδας στην ευρωζώνη θα είναι βαθύτατα «τοξική» για τις υπόλοιπες χώρες και θα οδηγήσει σε μαζική έξοδο κεφαλαίων από τις χώρες της ευρωζώνης. Ο κίνδυνος για την ευρωζώνη από την συνεχιζόμενη παραμονή της Ελλάδας θα αρχίσει να φαντάζει πολύ μεγαλύτερος από τις τυχόν επιπτώσεις μιάς εξόδου. Η έξοδος της Ελλάδας θα αρχίσει να θεωρείται ως «λύτρωση» και όχι πιά ως αρχή μεγαλυτέρων δεινών.

Περισσότερα

Protagon.gr

27 Αυγούστου 2012

Δεν υπάρχει καμία αμφιβολία ότι η αναμενόμενη τον Σεπτέμβριο(;) έκθεση της τρόικα θα παίξει καθοριστικό ρόλο τόσο στην εξέλιξη της ιστορίας της Ελλάδας όσο και στην εξέλιξη της ευρωζώνης.

Οσον αφορά την Ελλάδα τα πορίσματα της έκθεσης δεν θα επηρεάσουν απλά το αν θα δοθεί στην Ελλάδα επιμήκυνση όσον αφορά την επίτευξη των στόχων στους οποίους έχει συμφωνήσει. Αυτό είναι ένα τελείως δευτερεύον θέμα. Τα πορίσματα της έκθεσης θα παίξουν καθοριστικό ρόλο για την παραμονή της Ελλάδας στην ευρωζώνη. Οχι επειδή μία τυχόν αρνητική έκθεση θα δώσει την ευκαιρία στους «εχθρούς» να μας «τιμωρήσουν», όπως διατείνεται η λαϊκή σοφία, αλλά επειδή απλούστατα μια τέτοια εξέλιξη θα πείσει τις χρηματαγορές ότι η έξοδος από το ευρώ είναι πλέον μη αντιστρέψιμη. Αυτό σημαίνει σε απλά ρωμέικα ότι κανένας δυνητικός επενδυτής, Ελληνας ή ξένος, δεν πρόκειται να επενδύσει στην Ελλάδα γνωρίζοντας ότι το κεφάλαιο του μπορεί να μειωθεί από την μία ημέρα στην άλλη κατά πιθανώς 50%. Και από την στιγμή που δεν θα υπάρχουν επενδύσεις όσα (καθυστερημένα) μέτρα και να λάβεις, όσες δηλώσεις συμπαράστασης και να γίνονται από τους ξένους ηγέτες, ανάκαμψη δεν πρόκειται να υπάρξει. Με αποτέλεσμα την νομοτελειακή εγκατάλειψη του ευρώ.

Όμως μία αρνητική για την Ελλάδα έκθεση της τρόικα θα έχει σημαντικές επιπτώσεις και στην ευρωζώνη. Στον βαθμό που θα ενισχύσει τις προσδοκίες των αγορών για έξοδο της Ελλάδας από το ευρώ, η συνεχιζόμενη παραμονή της θα δρά τελείως αποσταθεροποιητικά για την υπόλοιπη ευρωζώνη. Το θέμα δεν είναι ότι δεν θα γίνονται μόνο επενδύσεις στην Ελλάδα αλλά ούτε και στην υπόλοιπη ευρωζώνη καθώς όλοι θα περιμένουν να δούν τις επιπτώσεις που θα έχει η προεξοφλούμενη έξοδος της Ελλάδας. Απ' αυτή λοιπόν την σκοπιά η συνεχιζόμενη μετά από μία αρνητική έκθεση παραμονή της Ελλάδας στην ευρωζώνη θα είναι βαθύτατα «τοξική» για τις υπόλοιπες χώρες και θα οδηγήσει σε μαζική έξοδο κεφαλαίων από τις χώρες της ευρωζώνης. Ο κίνδυνος για την ευρωζώνη από την συνεχιζόμενη παραμονή της Ελλάδας θα αρχίσει να φαντάζει πολύ μεγαλύτερος από τις τυχόν επιπτώσεις μιάς εξόδου. Η έξοδος της Ελλάδας θα αρχίσει να θεωρείται ως «λύτρωση» και όχι πιά ως αρχή μεγαλυτέρων δεινών.

Περισσότερα

Has ‘Europe’ Failed?

by Nicholas Sambanis

New York Times

August 26, 2012

Last week, European leaders met in Berlin amid new signs of an impending recession and an emerging consensus that Greece could leave the euro zone within a year — a move that would have dire consequences for the currency’s future.

There are many reasons behind the crisis, from corruption and collective irresponsibility in Greece to European institutional rigidities and the flawed concept of a monetary union without a fiscal union. But this is not just a story about profligate spending and rigid monetary policy. The European debt crisis is not just an economic crisis: it is an escalating identity conflict — an ethnic conflict.

The European Union was a political concept, designed to tame a bellicose Germany. Strong economic interdependence and a common European identity, it was thought, would be cultivated by the institutions of the union, as Europeans benefited from the economic prosperity that integration would create.

Elites could sell that concept to their publics as long as Europe prospered and had high international status. But the union has lost its shine. It is slowing down and aging. Its longtime ally, the United States, is shifting attention to East Asia. Its common defense policy is shallow.

More

New York Times

August 26, 2012

Last week, European leaders met in Berlin amid new signs of an impending recession and an emerging consensus that Greece could leave the euro zone within a year — a move that would have dire consequences for the currency’s future.

There are many reasons behind the crisis, from corruption and collective irresponsibility in Greece to European institutional rigidities and the flawed concept of a monetary union without a fiscal union. But this is not just a story about profligate spending and rigid monetary policy. The European debt crisis is not just an economic crisis: it is an escalating identity conflict — an ethnic conflict.

The European Union was a political concept, designed to tame a bellicose Germany. Strong economic interdependence and a common European identity, it was thought, would be cultivated by the institutions of the union, as Europeans benefited from the economic prosperity that integration would create.

Elites could sell that concept to their publics as long as Europe prospered and had high international status. But the union has lost its shine. It is slowing down and aging. Its longtime ally, the United States, is shifting attention to East Asia. Its common defense policy is shallow.

More

To πανεπιστήμιο της Βόννης, ο Σαμαράς και η Μέρκελ (Συνέντευξη του Manfred Neumann)

του Τάσου Τέλλογλου

Protagon.gr

27 Αυγούστου 2012

Τώρα που τελείωσε το τούρ του πρωθυπουργού στις ευρωπαϊκές πρωτεύουσες, όπου μεταξύ των άλλων είχε να παλέψει με τον εαυτό του στην αντιπολίτευση, κάτι που αναγνώρισε στο Βερολίνο («ουδείς αναμάρτητος», ίσως η πιο ανθρώπινη δημόσια φράση του στην περιοδεία) είναι καλό να ξανακοιτάξει κανείς τα «βασικά μεγέθη» και επιχειρήματα στη Γερμανία, έτσι όπως προκύπτουν από τη συζήτηση στην ίδια τη χώρα, τα κέντρα που ασκούν πραγματική εξουσία και διαμορφώνουν τη δημόσια αντιπαράθεση. Την ημέρα που ο κ Σαμαράς περνούσε την πόρτα της καγκελαρίας, ο Μάνφρεντ Νώυμαν (Manfred Neumann), ο πιο σημαντικός ίσως από τους καθηγητές οικονομικών, που συμβουλεύουν κέντρα εξουσίας στη Γερμανία, έπαιρνε δημόσια θέση για μία ακόμα φορά για την κρίση της Ευρωζώνης. Ο Νώυμαν εχει το προνόμιο να είναι ο επιβλέπων καθηγητής και αργότερα επικεφαλής στο Ινστιτούτο των δύο διαδοχικών διοικητών της γερμανικής κεντρικής Τράπεζας, του Αξελ Βέμπερ, τον οποίο η Μέρκελ τον προοριζε για διοικητή της Ευρωπαικής Κεντρικής Τράπεζας -και δέν εγινε- και του σημερινού διοικητή της γερμανικής κεντρικής Τράπεζας Γένς Βάηντμαν, πρώην οικονομικού της συμβουλου.

Μιλώντας στους Αντρέα Ρεξερ και Μάρκους Ζύντρα της Sueddeutsche Zeitung, ο Νώυμαν προτείνει μια Ελλάδα με διπλό νόμισμα, υποστηρίζει ότι είναι πιθανότερο να βγεί η Γερμανία απο το ευρώ απο το να εγκαταλείψει η Ιταλία το κοινό νόμισμα και προειδοποιεί οτι «ο γερμανός εκατομμυριούχος θα ρωτά πάντα πόσο φόρο πληρώνει ο Ελληνας εκατομμυριούχος» προσθέτοντας οτι η Ελλάδα δέν εχει ισχυρή κυβέρνηση και ισως για αυτό αναγκαστεί να εγκαταλείψει το ευρώ.

Περισσότερα

Protagon.gr

27 Αυγούστου 2012

Τώρα που τελείωσε το τούρ του πρωθυπουργού στις ευρωπαϊκές πρωτεύουσες, όπου μεταξύ των άλλων είχε να παλέψει με τον εαυτό του στην αντιπολίτευση, κάτι που αναγνώρισε στο Βερολίνο («ουδείς αναμάρτητος», ίσως η πιο ανθρώπινη δημόσια φράση του στην περιοδεία) είναι καλό να ξανακοιτάξει κανείς τα «βασικά μεγέθη» και επιχειρήματα στη Γερμανία, έτσι όπως προκύπτουν από τη συζήτηση στην ίδια τη χώρα, τα κέντρα που ασκούν πραγματική εξουσία και διαμορφώνουν τη δημόσια αντιπαράθεση. Την ημέρα που ο κ Σαμαράς περνούσε την πόρτα της καγκελαρίας, ο Μάνφρεντ Νώυμαν (Manfred Neumann), ο πιο σημαντικός ίσως από τους καθηγητές οικονομικών, που συμβουλεύουν κέντρα εξουσίας στη Γερμανία, έπαιρνε δημόσια θέση για μία ακόμα φορά για την κρίση της Ευρωζώνης. Ο Νώυμαν εχει το προνόμιο να είναι ο επιβλέπων καθηγητής και αργότερα επικεφαλής στο Ινστιτούτο των δύο διαδοχικών διοικητών της γερμανικής κεντρικής Τράπεζας, του Αξελ Βέμπερ, τον οποίο η Μέρκελ τον προοριζε για διοικητή της Ευρωπαικής Κεντρικής Τράπεζας -και δέν εγινε- και του σημερινού διοικητή της γερμανικής κεντρικής Τράπεζας Γένς Βάηντμαν, πρώην οικονομικού της συμβουλου.

Μιλώντας στους Αντρέα Ρεξερ και Μάρκους Ζύντρα της Sueddeutsche Zeitung, ο Νώυμαν προτείνει μια Ελλάδα με διπλό νόμισμα, υποστηρίζει ότι είναι πιθανότερο να βγεί η Γερμανία απο το ευρώ απο το να εγκαταλείψει η Ιταλία το κοινό νόμισμα και προειδοποιεί οτι «ο γερμανός εκατομμυριούχος θα ρωτά πάντα πόσο φόρο πληρώνει ο Ελληνας εκατομμυριούχος» προσθέτοντας οτι η Ελλάδα δέν εχει ισχυρή κυβέρνηση και ισως για αυτό αναγκαστεί να εγκαταλείψει το ευρώ.

Περισσότερα

Sunday, August 26, 2012

The German people will decide Europe's fate

by Hans Kundnani

Guardian

August 26, 2012

As speculation about a Greek exit from the eurozone continues, Germany is pushing ahead with plans for a new treaty that will transform the European Union.

According to this week's Spiegel, Angela Merkel wants European leaders to agree by the end of the year to hold a constitutional convention in order to fashion a new legal basis for the EU – even though most other member states are opposed to the idea of another tortuous and risky treaty negotiation so soon after the failed European constitution and the Lisbon treaty. The plan could dramatically reshape the EU in Germany's image – or lead to it falling apart.

On Friday Merkel rejected Greece's plea for more time to implement austerity measures while affirming that she still wanted it to remain in the euro. There had been some signs that German anger about Greece had dissipated – Bild published a surprisingly positive interview with the Greek prime minister, Antonis Samaras, last week – but at the same time confidence is growing that a Greek exit from the euro could be contained. Figures such as Volker Kauder, the parliamentary leader of the Christian Democrats, and Philipp Rösler, vice-chancellor and leader of the Free Democrats, the junior partner in Merkel's coalition government, have said they no longer fear a Greek exit.

More

Guardian

August 26, 2012

As speculation about a Greek exit from the eurozone continues, Germany is pushing ahead with plans for a new treaty that will transform the European Union.

According to this week's Spiegel, Angela Merkel wants European leaders to agree by the end of the year to hold a constitutional convention in order to fashion a new legal basis for the EU – even though most other member states are opposed to the idea of another tortuous and risky treaty negotiation so soon after the failed European constitution and the Lisbon treaty. The plan could dramatically reshape the EU in Germany's image – or lead to it falling apart.

On Friday Merkel rejected Greece's plea for more time to implement austerity measures while affirming that she still wanted it to remain in the euro. There had been some signs that German anger about Greece had dissipated – Bild published a surprisingly positive interview with the Greek prime minister, Antonis Samaras, last week – but at the same time confidence is growing that a Greek exit from the euro could be contained. Figures such as Volker Kauder, the parliamentary leader of the Christian Democrats, and Philipp Rösler, vice-chancellor and leader of the Free Democrats, the junior partner in Merkel's coalition government, have said they no longer fear a Greek exit.

More

Banks’ continuing damage to Europe

Financial Times

Editorial

August 26, 2012

The eurozone debt crisis was caused more by private credit excesses – particularly in the banking sector – than by public sector profligacy. The damage that a dysfunctional banking system has inflicted on Europe’s economy is not finished but now the banks are lending too little where earlier they were lending too much.

A new study from the Central Bank of Ireland reveals the difficulties small and medium enterprises in Ireland – but also in other eurozone peripheral countries – face in accessing bank credit. The paper uses European Central Bank and other data to show that Irish SMEs’ demand for credit is comparable to the average across the monetary union. But the number of businesses whose loan applications are rejected, or which face harsh or prohibitive terms or do not even apply for credit because they expect to be turned down, is among the highest in the eurozone.

This story matches that of other troubled euro members such as Spain and Greece. Outside construction, Spain retains many competitive companies in the private non-financial sector. But those that can viably expand complain that banks no longer give the necessary credit. Thus, with a quarter of the labour force unemployed, companies that could hire are prevented from doing so.

The Greek economy is a much bigger disaster than Spain’s. Even in Greece, however, some companies can do business – especially those involved in exports that benefit from the austerity programme’s painful grinding down of labour costs. But foreign suppliers and clients worried about Athens leaving the euro offer no forbearance to Greek companies, which are instead becoming completely dependent on domestic credit from a still-insolvent banking system.

More

Editorial

August 26, 2012

The eurozone debt crisis was caused more by private credit excesses – particularly in the banking sector – than by public sector profligacy. The damage that a dysfunctional banking system has inflicted on Europe’s economy is not finished but now the banks are lending too little where earlier they were lending too much.

A new study from the Central Bank of Ireland reveals the difficulties small and medium enterprises in Ireland – but also in other eurozone peripheral countries – face in accessing bank credit. The paper uses European Central Bank and other data to show that Irish SMEs’ demand for credit is comparable to the average across the monetary union. But the number of businesses whose loan applications are rejected, or which face harsh or prohibitive terms or do not even apply for credit because they expect to be turned down, is among the highest in the eurozone.

This story matches that of other troubled euro members such as Spain and Greece. Outside construction, Spain retains many competitive companies in the private non-financial sector. But those that can viably expand complain that banks no longer give the necessary credit. Thus, with a quarter of the labour force unemployed, companies that could hire are prevented from doing so.

The Greek economy is a much bigger disaster than Spain’s. Even in Greece, however, some companies can do business – especially those involved in exports that benefit from the austerity programme’s painful grinding down of labour costs. But foreign suppliers and clients worried about Athens leaving the euro offer no forbearance to Greek companies, which are instead becoming completely dependent on domestic credit from a still-insolvent banking system.

More

The ECB must still do its bit to help solve the crisis

by Wolfgang Münchau

Financial Times

August 26, 2012

Can the European Central Bank solve the eurozone crisis on its own? The answer is clearly No. But without ECB intervention, the crisis is insoluble. So what should the goals of such an operation be? And how should this be accomplished?

I would consider three goals, subject to two constraints. The first and most important is to get rid of market expectations of a eurozone break up. Whatever the ECB’s governing council decides on September 6, it must be big enough to squash expectations that Spain or Italy will leave the eurozone. A Greek departure is different. This programme is not about Greece.

Second, it must be part of an overall resolution strategy. Mario Draghi is right to say that ECB support should depend on an official application for support. But this is when it gets tricky. How will the president of the ECB adjust his programme if a country fails to meet the criteria? And who decides?

Third, he has to address the issue of investor subordination. If the ECB’s holdings are considered senior to those of other investors, it may never be possible to get private investors back into those countries.

More

Financial Times

August 26, 2012

Can the European Central Bank solve the eurozone crisis on its own? The answer is clearly No. But without ECB intervention, the crisis is insoluble. So what should the goals of such an operation be? And how should this be accomplished?

I would consider three goals, subject to two constraints. The first and most important is to get rid of market expectations of a eurozone break up. Whatever the ECB’s governing council decides on September 6, it must be big enough to squash expectations that Spain or Italy will leave the eurozone. A Greek departure is different. This programme is not about Greece.

Second, it must be part of an overall resolution strategy. Mario Draghi is right to say that ECB support should depend on an official application for support. But this is when it gets tricky. How will the president of the ECB adjust his programme if a country fails to meet the criteria? And who decides?

Third, he has to address the issue of investor subordination. If the ECB’s holdings are considered senior to those of other investors, it may never be possible to get private investors back into those countries.

More

Τελευταία ευκαιρία εξυγίανσης του Δημοσίου

της Μιράντας Ξαφά

Καθημερινή

26 Αυγούστου 2012

Τη στιγμή που γράφεται αυτό το άρθρο δεν έχει ακόμα συναντηθεί ο πρωθυπουργός κ. Σαμαράς με την κ. Μέρκελ και τον κ. Ολάντ, είναι όμως προφανές ότι τίποτε δεν πρόκειται να συμφωνηθεί πριν η κυβέρνηση ξαναφέρει το πρόγραμμα σταθεροποίησης σε τροχιά και εξασφαλίσει τη θετική αξιολόγηση της τρόικας. Είναι επομένως αποκαρδιωτικό ότι έξι μήνες μετά την υπογραφή του δεύτερου Μνημονίου, οι ίδιοι που το υπέγραψαν αναζητούν ακόμη τα 11,6 δισ. ευρώ σε περικοπές δαπανών που συμφώνησαν. Οι Ευρωπαίοι εταίροι μας και το ΔΝΤ δεν πρόκειται να διαπραγματευτούν αλλαγή των όρων της συμφωνίας με την Ελλάδα αν δεν έχουν πειστεί ότι το έλλειμμα θα γίνει σχετικά σύντομα πλεόνασμα ώστε να μη χρειαστεί και τρίτη διάσωση μετά από λίγα χρόνια.

Το Μνημόνιο μας προσφέρει μια μοναδική ευκαιρία να προχωρήσουμε στην αναδόμηση της οικονομίας και του κράτους με την οικονομική και τεχνική υποστήριξη των εταίρων μας και του ΔΝΤ. Πρέπει επί τέλους η δημόσια διοίκηση να μπει στην υπηρεσία των πολιτών και όχι των συντεχνιών και συνδικαλιστών που μάχονται για καθαρά ιδιοτελείς λόγους στο όνομα του δημοσίου συμφέροντος. Πρέπει οι αγορές να απελευθερωθούν και η γραφειοκρατία να απαλειφθεί για να μπορέσουμε να αξιοποιήσουμε τα συγκριτικά πλεονεκτήματα της χώρας. Μέτρα άμεσης απόδοσης για την επιδιωκόμενη ανάκαμψη της οικονομίας είναι η απεμπλοκή επενδυτικών σχεδίων σε ενέργεια, ΑΠΕ, ανακύκλωση, τουρισμό κ.λπ. από τα γρανάζια της γραφειοκρατίας, όπως προσπαθεί να κάνει ο κ. Χατζηδάκης. Συγχρόνως, χρειάζεται επανεξέταση των διαδικασιών από μηδενική βάση και θεσμοθέτηση απλών, κατανοητών και λίγων κανόνων. Από τη στιγμή που εγκρίνεται μια επένδυση, κανείς δεν πρέπει να έχει το δικαίωμα να τη σταματήσει.

Το πρόσφατο ηλεκτρονικό βιβλίο του κ. Πάγκαλου Τα φάγαμε όλοι μαζί μας φέρνει αντιμέτωπους με τις πρακτικές και νοοτροπίες που κατέστησαν δυνατή τη χρεοκοπία - την ηθική κατάπτωση, την απαξίωση των θεσμών, την έλλειψη λογοδοσίας και υπεύθυνης ηγεσίας. Αλόγιστες παροχές που δόθηκαν κάτω από την πίεση των συνδικάτων, σπατάλη και διαφθορά που έμειναν ατιμώρητες, διαρκείς απεργιακές κινητοποιήσεις και διαδηλώσεις για τη διατήρηση των κεκτημένων, συνθέτουν την εικόνα της Ελλάδας της μεταπολίτευσης. Το πολιτικό προσωπικό της χώρας προτίμησε να κλείνει τα μάτια σε απαράδεκτες πρακτικές για να αποφύγει τις σκληρές επιλογές που οι συνθήκες επέβαλλαν (π.χ. Καραμανλής, 2004: «Δεν θα ανοίξω το ασφαλιστικό την πρώτη τετραετία»). Το βιβλίο δείχνει με γλαφυρό τρόπο πόσο λανθασμένη είναι η άποψη ότι η σημερινή κρίση μπορεί να ξεπεραστεί χωρίς τη ριζική αναθεώρηση των αξιών και συμπεριφορών που μας έφεραν εδώ.

Περισσότερα

Θεόδωρου Γ. Πάγκαλου, Τα Φάγαμε Όλοι Μαζί

Καθημερινή

26 Αυγούστου 2012

Τη στιγμή που γράφεται αυτό το άρθρο δεν έχει ακόμα συναντηθεί ο πρωθυπουργός κ. Σαμαράς με την κ. Μέρκελ και τον κ. Ολάντ, είναι όμως προφανές ότι τίποτε δεν πρόκειται να συμφωνηθεί πριν η κυβέρνηση ξαναφέρει το πρόγραμμα σταθεροποίησης σε τροχιά και εξασφαλίσει τη θετική αξιολόγηση της τρόικας. Είναι επομένως αποκαρδιωτικό ότι έξι μήνες μετά την υπογραφή του δεύτερου Μνημονίου, οι ίδιοι που το υπέγραψαν αναζητούν ακόμη τα 11,6 δισ. ευρώ σε περικοπές δαπανών που συμφώνησαν. Οι Ευρωπαίοι εταίροι μας και το ΔΝΤ δεν πρόκειται να διαπραγματευτούν αλλαγή των όρων της συμφωνίας με την Ελλάδα αν δεν έχουν πειστεί ότι το έλλειμμα θα γίνει σχετικά σύντομα πλεόνασμα ώστε να μη χρειαστεί και τρίτη διάσωση μετά από λίγα χρόνια.

Το Μνημόνιο μας προσφέρει μια μοναδική ευκαιρία να προχωρήσουμε στην αναδόμηση της οικονομίας και του κράτους με την οικονομική και τεχνική υποστήριξη των εταίρων μας και του ΔΝΤ. Πρέπει επί τέλους η δημόσια διοίκηση να μπει στην υπηρεσία των πολιτών και όχι των συντεχνιών και συνδικαλιστών που μάχονται για καθαρά ιδιοτελείς λόγους στο όνομα του δημοσίου συμφέροντος. Πρέπει οι αγορές να απελευθερωθούν και η γραφειοκρατία να απαλειφθεί για να μπορέσουμε να αξιοποιήσουμε τα συγκριτικά πλεονεκτήματα της χώρας. Μέτρα άμεσης απόδοσης για την επιδιωκόμενη ανάκαμψη της οικονομίας είναι η απεμπλοκή επενδυτικών σχεδίων σε ενέργεια, ΑΠΕ, ανακύκλωση, τουρισμό κ.λπ. από τα γρανάζια της γραφειοκρατίας, όπως προσπαθεί να κάνει ο κ. Χατζηδάκης. Συγχρόνως, χρειάζεται επανεξέταση των διαδικασιών από μηδενική βάση και θεσμοθέτηση απλών, κατανοητών και λίγων κανόνων. Από τη στιγμή που εγκρίνεται μια επένδυση, κανείς δεν πρέπει να έχει το δικαίωμα να τη σταματήσει.

Το πρόσφατο ηλεκτρονικό βιβλίο του κ. Πάγκαλου Τα φάγαμε όλοι μαζί μας φέρνει αντιμέτωπους με τις πρακτικές και νοοτροπίες που κατέστησαν δυνατή τη χρεοκοπία - την ηθική κατάπτωση, την απαξίωση των θεσμών, την έλλειψη λογοδοσίας και υπεύθυνης ηγεσίας. Αλόγιστες παροχές που δόθηκαν κάτω από την πίεση των συνδικάτων, σπατάλη και διαφθορά που έμειναν ατιμώρητες, διαρκείς απεργιακές κινητοποιήσεις και διαδηλώσεις για τη διατήρηση των κεκτημένων, συνθέτουν την εικόνα της Ελλάδας της μεταπολίτευσης. Το πολιτικό προσωπικό της χώρας προτίμησε να κλείνει τα μάτια σε απαράδεκτες πρακτικές για να αποφύγει τις σκληρές επιλογές που οι συνθήκες επέβαλλαν (π.χ. Καραμανλής, 2004: «Δεν θα ανοίξω το ασφαλιστικό την πρώτη τετραετία»). Το βιβλίο δείχνει με γλαφυρό τρόπο πόσο λανθασμένη είναι η άποψη ότι η σημερινή κρίση μπορεί να ξεπεραστεί χωρίς τη ριζική αναθεώρηση των αξιών και συμπεριφορών που μας έφεραν εδώ.

Περισσότερα

Θεόδωρου Γ. Πάγκαλου, Τα Φάγαμε Όλοι Μαζί

Οι νέοι βιώνουν χειρότερα την κρίση

του Ιάσονα Μανωλόπουλου

Καθημερινή

26 Αυγούστου 2012

Χώρες με βαθιά προβλήματα, όπως η Ελλάδα, που διακρίνονται για τους λαϊκιστές πολιτικούς τους ποτέ δεν ξεμένουν από «πολέμους»... Η πολιτικολογία επικεντρώνεται κυρίως στις συγκρούσεις ανάμεσα στην Ελλάδα και την τρόικα, τον ιδιωτικό και τον δημόσιο τομέα, την Αθήνα και την επαρχία, τους ντόπιους και τους μετανάστες.

Υπάρχει μια τεράστια σύγκρουση που υποβόσκει χωρίς να πολυσυζητιέται: η σύγκρουση ανάμεσα στις γενεές. Ωφελημένοι από την πιστωτική έκρηξη, την άνοδο στις τιμές των ακινήτων και τα κλειστά επαγγέλματα, ήταν οι μεγαλύτεροι σε ηλικία. Τις δυσμενείς επιπτώσεις του χρέους, της εκτύπωσης χρήματος και των μέτρων λιτότητας τις βιώνουν δυσανάλογα οι νέοι.

Αυτό το μοτίβο το βλέπουμε σε ολόκληρη τη Δύση. Οπως παρατήρησε το 1790 ο θεωρητικός της πολιτικής επιστήμης, Εντμουντ Μπερκ: «Η κοινωνία είναι όντως ένα συμβόλαιο. Το κράτος είναι ένας συνεταιρισμός, όχι μόνο ανάμεσα στους ζωντανούς, αλλά ανάμεσα στους ζωντανούς, τους νεκρούς και σε όσους πρόκειται να γεννηθούν».

Στον δυτικό κόσμο αρχίζουν συζητήσεις για το αν έχει αθετηθεί το κοινωνικό συμβόλαιο μεταξύ των γενεών. Μήπως η γενιά του «baby boom» (της μεταπολεμικής έκρηξης των γεννήσεων) -η «γενιά του ’60», όπως ονομάζεται στην Ελλάδα- έχει φερθεί με εξαιρετικά εγωιστικό τρόπο; Υποστηρίζεται ότι, αφού ωφελήθηκε από τη δωρεάν παιδεία, τις καλές υπηρεσίες υγείας και τις διαρκώς αυξανόμενες συντάξεις, τώρα, που αποτελεί την ομάδα ψηφοφόρων που επηρεάζει περισσότερο από κάθε άλλη την κυβέρνηση, στερεί τα οφέλη αυτά από τη νεότερη γενιά. Η τάση αυτή μπορεί να παγιωθεί, αφού στις περισσότερες χώρες είναι πιθανότερο να ψηφίζουν οι μεγαλύτεροι. Μήπως οδεύουμε, λοιπόν, προς μια γεροντοκρατία - μια κοινωνία όπου κυβερνούν οι ηλικιωμένοι και για τους ηλικιωμένους; Υπάρχουν ενδείξεις ότι μια ολόκληρη γενιά έδρασε σαν τεράστια συνδικαλιστική οργάνωση, εξασφαλίζοντας για λογαριασμό της δυσανάλογα γενναιόδωρα οφέλη σε βάρος άλλων. Ωστόσο, σχεδόν σε κάθε συζήτηση περί ανισότητας ανάμεσα στις γενεές ελλοχεύει ο κίνδυνος της υπεραπλούστευσης, δεδομένου ότι στο εσωτερικό κάθε γενεάς παρατηρούνται τεράστιες παραλλαγές.

Περισσότερα

Καθημερινή

26 Αυγούστου 2012

Χώρες με βαθιά προβλήματα, όπως η Ελλάδα, που διακρίνονται για τους λαϊκιστές πολιτικούς τους ποτέ δεν ξεμένουν από «πολέμους»... Η πολιτικολογία επικεντρώνεται κυρίως στις συγκρούσεις ανάμεσα στην Ελλάδα και την τρόικα, τον ιδιωτικό και τον δημόσιο τομέα, την Αθήνα και την επαρχία, τους ντόπιους και τους μετανάστες.

Υπάρχει μια τεράστια σύγκρουση που υποβόσκει χωρίς να πολυσυζητιέται: η σύγκρουση ανάμεσα στις γενεές. Ωφελημένοι από την πιστωτική έκρηξη, την άνοδο στις τιμές των ακινήτων και τα κλειστά επαγγέλματα, ήταν οι μεγαλύτεροι σε ηλικία. Τις δυσμενείς επιπτώσεις του χρέους, της εκτύπωσης χρήματος και των μέτρων λιτότητας τις βιώνουν δυσανάλογα οι νέοι.

Αυτό το μοτίβο το βλέπουμε σε ολόκληρη τη Δύση. Οπως παρατήρησε το 1790 ο θεωρητικός της πολιτικής επιστήμης, Εντμουντ Μπερκ: «Η κοινωνία είναι όντως ένα συμβόλαιο. Το κράτος είναι ένας συνεταιρισμός, όχι μόνο ανάμεσα στους ζωντανούς, αλλά ανάμεσα στους ζωντανούς, τους νεκρούς και σε όσους πρόκειται να γεννηθούν».

Στον δυτικό κόσμο αρχίζουν συζητήσεις για το αν έχει αθετηθεί το κοινωνικό συμβόλαιο μεταξύ των γενεών. Μήπως η γενιά του «baby boom» (της μεταπολεμικής έκρηξης των γεννήσεων) -η «γενιά του ’60», όπως ονομάζεται στην Ελλάδα- έχει φερθεί με εξαιρετικά εγωιστικό τρόπο; Υποστηρίζεται ότι, αφού ωφελήθηκε από τη δωρεάν παιδεία, τις καλές υπηρεσίες υγείας και τις διαρκώς αυξανόμενες συντάξεις, τώρα, που αποτελεί την ομάδα ψηφοφόρων που επηρεάζει περισσότερο από κάθε άλλη την κυβέρνηση, στερεί τα οφέλη αυτά από τη νεότερη γενιά. Η τάση αυτή μπορεί να παγιωθεί, αφού στις περισσότερες χώρες είναι πιθανότερο να ψηφίζουν οι μεγαλύτεροι. Μήπως οδεύουμε, λοιπόν, προς μια γεροντοκρατία - μια κοινωνία όπου κυβερνούν οι ηλικιωμένοι και για τους ηλικιωμένους; Υπάρχουν ενδείξεις ότι μια ολόκληρη γενιά έδρασε σαν τεράστια συνδικαλιστική οργάνωση, εξασφαλίζοντας για λογαριασμό της δυσανάλογα γενναιόδωρα οφέλη σε βάρος άλλων. Ωστόσο, σχεδόν σε κάθε συζήτηση περί ανισότητας ανάμεσα στις γενεές ελλοχεύει ο κίνδυνος της υπεραπλούστευσης, δεδομένου ότι στο εσωτερικό κάθε γενεάς παρατηρούνται τεράστιες παραλλαγές.

Περισσότερα

Για την αυτογνωσία μας

του Θάνου Βερέμη

Καθημερινή

26 Αυγούστου 2012

Oυδέν κακόν αμιγές καλού. H δημοσιονομική και κοινωνική κρίση που ζούμε προκάλεσε την πιο γόνιμη συζήτηση για το ελληνικό οικονομικό και κοινωνικό φαινόμενο από την εποχή της πρώτης μεταπολεμικής διετίας. H δυσπραγία μας, απαλλαγμένη από τη διάσπαση που προκαλούσαν στην προσοχή των ειδικών οι συγκυρίες της ανασυγκρότησης, του ανένδοτου αγώνα, της δικτατορίας και της μεταπολιτευτικής ευζωίας, μας ανάγκασε επιτέλους να εγκύψουμε στις δομικές μας αδυναμίες. O συλλογικός τόμος Aπρονοησία και νέμεση. Eλληνική κρίση 2001-2011 (The Athens Review of Books, 2012) με επιμέλεια Mανώλη Bασιλάκη, αποτελεί κιβωτό αυτογνωσίας. Oι μελέτες που περιέχονται στον τόμο αυτό έχουν ξεπεράσει δεξιές και αριστερές αγκυλώσεις για να πουν τα πράγματα με το όνομά τους. Mερικοί από τους συνεργάτες βρέθηκαν σε δημόσιες θέσεις, ένας μάλιστα από αυτούς είναι ο σημερινός υπουργός Oικονομικών, όμως οι περισσότεροι διέφυγαν την προσοχή των πολιτικών μας ηγετών. Oλοι τους προσφέρουν τον λίθο τους για να οικοδομηθεί συστηματικά η ερμηνεία τού τι πήγε στραβά σε τούτο τον τόπο.

Πολλοί επισημαίνουν την εξάρτηση μεγάλου τμήματος της κοινωνίας από το κράτος, ώστε να σοβεί μια επικίνδυνη αντιπαράθεση των ομάδων που επωφελούνται από το status quo με εκείνους που καταβάλλουν ακέραιο το κόστος αυτής της ανωμαλίας.

Kαι ενώ σαν τους Mοιραίους του Bάρναλη περιμένουμε τον παράκλητο ηγέτη που θα μας σώσει από το σημερινό αδιέξοδο, πλησιάζουμε επικίνδυνα το ενδεχόμενο «μιας βίαιης εξαθλίωσης» (Mιχ. Mητσόπουλος, σ. 297).

Περισσότερα

Καθημερινή

26 Αυγούστου 2012

Oυδέν κακόν αμιγές καλού. H δημοσιονομική και κοινωνική κρίση που ζούμε προκάλεσε την πιο γόνιμη συζήτηση για το ελληνικό οικονομικό και κοινωνικό φαινόμενο από την εποχή της πρώτης μεταπολεμικής διετίας. H δυσπραγία μας, απαλλαγμένη από τη διάσπαση που προκαλούσαν στην προσοχή των ειδικών οι συγκυρίες της ανασυγκρότησης, του ανένδοτου αγώνα, της δικτατορίας και της μεταπολιτευτικής ευζωίας, μας ανάγκασε επιτέλους να εγκύψουμε στις δομικές μας αδυναμίες. O συλλογικός τόμος Aπρονοησία και νέμεση. Eλληνική κρίση 2001-2011 (The Athens Review of Books, 2012) με επιμέλεια Mανώλη Bασιλάκη, αποτελεί κιβωτό αυτογνωσίας. Oι μελέτες που περιέχονται στον τόμο αυτό έχουν ξεπεράσει δεξιές και αριστερές αγκυλώσεις για να πουν τα πράγματα με το όνομά τους. Mερικοί από τους συνεργάτες βρέθηκαν σε δημόσιες θέσεις, ένας μάλιστα από αυτούς είναι ο σημερινός υπουργός Oικονομικών, όμως οι περισσότεροι διέφυγαν την προσοχή των πολιτικών μας ηγετών. Oλοι τους προσφέρουν τον λίθο τους για να οικοδομηθεί συστηματικά η ερμηνεία τού τι πήγε στραβά σε τούτο τον τόπο.

Πολλοί επισημαίνουν την εξάρτηση μεγάλου τμήματος της κοινωνίας από το κράτος, ώστε να σοβεί μια επικίνδυνη αντιπαράθεση των ομάδων που επωφελούνται από το status quo με εκείνους που καταβάλλουν ακέραιο το κόστος αυτής της ανωμαλίας.

Kαι ενώ σαν τους Mοιραίους του Bάρναλη περιμένουμε τον παράκλητο ηγέτη που θα μας σώσει από το σημερινό αδιέξοδο, πλησιάζουμε επικίνδυνα το ενδεχόμενο «μιας βίαιης εξαθλίωσης» (Mιχ. Mητσόπουλος, σ. 297).

Περισσότερα

Saturday, August 25, 2012

Spetses, the tycoons' playground where gulf between rich and poor grows wider

by Vanessa Thorpe

Guardian

August 25, 2012

On a jetty alongside the town beach a loud phone call disturbs the peace of a handful of Spetses residents lying in the sun before taking their daily swim – one free pleasure that is still available to all. A rich weekender from Athens booms ostentatiously into his mobile, directing a man behind the wheel of a sizeable speedboat. "Just ignore the line of buoys," he says, "and steer straight over to me so we can talk." The instruction provokes a furious reaction from locals, who yell out angrily that boats are never allowed to come so close to the swimmers. A nasty row flares up – a sign of growing social tensions on an island where poor locals live cheek-by-jowl with the holidaymaking rich.

Antonis Samaras, the Greek prime minister, spent last week pleading with European leaders for more time to implement the severe austerity programme that is, ultimately, the condition for Greece remaining in the euro. Back home, and on islands such as Spetses, those well-off Greeks who remain financially cushioned from the effects of the deepening crisis, and from the fresh austerity measures due to be imposed next month, are the targets of growing fury.

The Saronic isle, with its pretty horse buggies and flowery villas, has been chosen as the location for a new Greek tourism advert, designed to reassure international visitors that the beaches and the bobbing fishing boats are still waiting for them, despite the economic meltdown. Yet the place is also a microcosm of the country's troubles: 30 square miles that encompass unimaginably big gaps in income.

While Athenians can enjoy browsing in the expensive deli that has replaced the souvlaki outlet in the square, the majority of Spetsiots can no longer afford to eat in local restaurants. The price of food in supermarkets and shops has soared.

More

Guardian

August 25, 2012

On a jetty alongside the town beach a loud phone call disturbs the peace of a handful of Spetses residents lying in the sun before taking their daily swim – one free pleasure that is still available to all. A rich weekender from Athens booms ostentatiously into his mobile, directing a man behind the wheel of a sizeable speedboat. "Just ignore the line of buoys," he says, "and steer straight over to me so we can talk." The instruction provokes a furious reaction from locals, who yell out angrily that boats are never allowed to come so close to the swimmers. A nasty row flares up – a sign of growing social tensions on an island where poor locals live cheek-by-jowl with the holidaymaking rich.

Antonis Samaras, the Greek prime minister, spent last week pleading with European leaders for more time to implement the severe austerity programme that is, ultimately, the condition for Greece remaining in the euro. Back home, and on islands such as Spetses, those well-off Greeks who remain financially cushioned from the effects of the deepening crisis, and from the fresh austerity measures due to be imposed next month, are the targets of growing fury.